THE NAVY DAYS

(and Years) OF FRED A. SKELLIE, JR.

We must continually work for peace at all times, but realistically, we must have strong modern armed forces for protection of our land and our freedom.

As I entered college at Tulane University in New Orleans in 1938, I expected to have a peaceful life, but just to hedge a little I decided to join the Navel R.O.T.C. (Reserve Officers Training Corp.). Having been raised on the Mississippi Gulf Coast in Long Beach, MS, just two blocks from the Gulf of Mexico, and having enjoyed the water activity of swimming and boating, I felt that the Navy was for me.

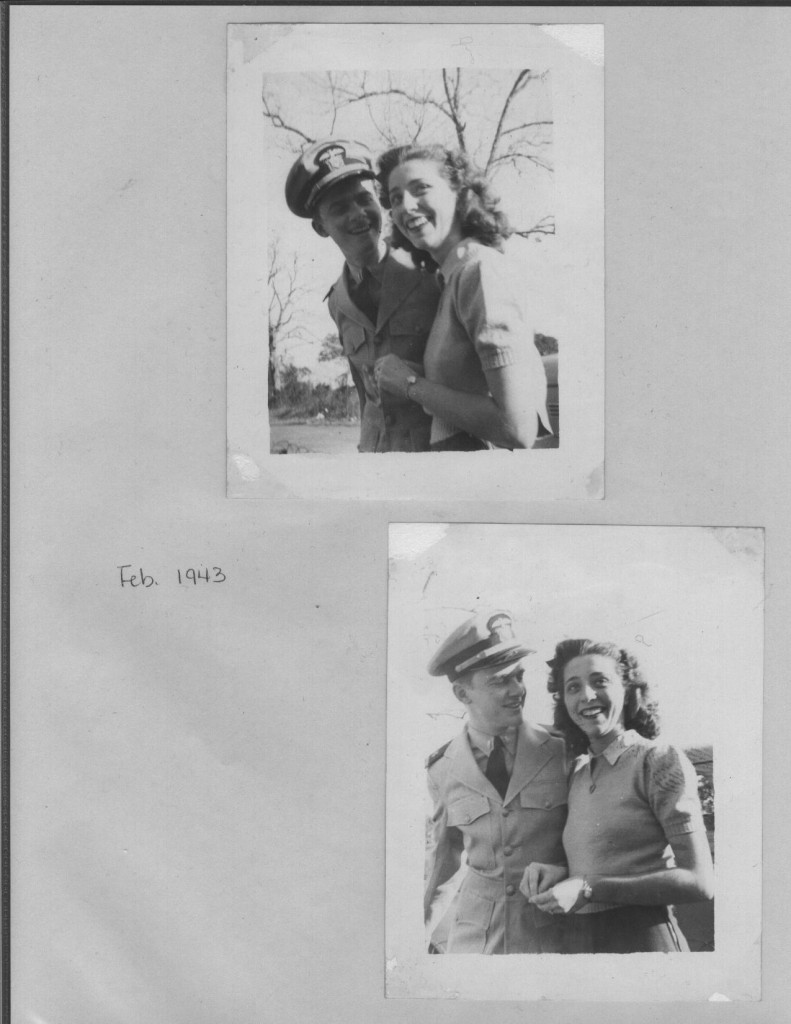

The Naval Course was for three hours each week – learning about seamanship, gunnery, navigation, etc. We marched at halftime during football games and in Mardi Gras parades. In the summer of l939, our ROTC group went on a summer cruise with other ROTC college groups aboard the old battleship Wyoming, then a training ship. Our first stop was Havana, Cuba. We had a pleasant time visiting the fort at the entrance to the harbor. Upon leaving the fort, I reached back into my memory of first year Spanish and told the guard “adios”. He responded with a “goodbye”. Before leaving Cuba, I mailed a card to my 15 year old girl friend, Lucille McPherson, (who later became my wife). The card was attached to a small sack of oats and said “Sowing Wild Oats”. Later Lucille told me that she showed the card to her mother and asked for an explanation. Her mother cracked up and then explained!

Our next stop was New York City, where we visited the World Fair exhibits. Then on to Boston to march in the “Bunker Hill” parade celebration. Next we headed back south to New Orleans. ‘Twas a great first Navy cruise and we never fired a shot!

Lucille’s family had moved from Atlanta, to Long Beach, MS in 1938, when her father was very ill with cancer of the liver. Just before he died, the family moved back to Birmingham, where his doctor lived. Mr. McPherson died shortly after the move and then the family moved to Tuscaloosa, AL. That way Lucille’s sister, Lillian Anne, could attend the University of Alabama as a day student. Lucille was then a senior in high school. During all this time, Lucille and I wrote weekly letters to each other. In 1941, Lucille and her mother moved to Gulfport and we began going together pretty steadily- that is as often as I could come over from New Orleans.

I graduated from Tulane in June 1942, but my orders for Navy duty did not come through until October, when I was assigned to the Galveston Naval base for temporary duty. Lucille & I became engaged. When my next orders arrived, I was to report in about 3 weeks for a month’s training in Miami’s Sub-chaser Training Center and that sounded like a good place for an extended honeymoon.

We were married at St. Peter’s by the Sea Episcopal Church (Lucille’s church) in Gulfport on March 29, 1943. We had a very short honeymoon in New Orleans and then headed back to Galveston for a few more weeks. A day or so later, I felt ill and was running a high temperature, so Lucille went downtown to shop for more bed linen (we only had one set) and fainted while shopping. When she returned we called the Naval base doctor who came to our apartment to check on us. He quickly looked us over, laughed and said that you two are going to get to know each other really well rather quickly, as you have the red measles. He said that he would have to quarantine both of us in our apartment for a week to ten days. We did get to know each other very well. Lucille later found that we were exposed to measles by one of her girl friends at our wedding.

Orders for my next assignment finally came and we headed for Miami on the train. We rented an apartment in North Miami.

One day Lucille was hanging out some clothes in the back yard and heard a rattle, which was coming from a rattlesnake by the clothesline. Back into the apartment she ran- and that was the end of outside clothes drying!

We stayed in Miami for two months, the last month I only had to call in each day to see if my orders had come for my next duty and then we were free to head for the beach or whatever we wanted to do.

The good times finally ended and I was ordered to a destroyer with homeport in Boston. We had a tearful parting in Jacksonville, with Lucille heading to a train to Gulfport, to stay with her mother.

My home for the next two plus years was aboard the destroyer U.S.S. Rodman (DD-456). One of my first duties was to supervise some painting of walls in the mess hall- the paint job looked very good. We had a movie in the mess hall that night and one of the sailors had his feet propped up on the cleanly painted wall and I said “Sailor get your feet off the wall”- I was laughed at as I quickly remembered it was a “bulkhead”, not a wall!

Our normal complement of personnel was around twenty officers and two hundred and fifty seamen. Our first assignment was to protect the new battleship Iowa from German submarines while on her “shake down” cruise in the North Atlantic. We left Boston Harbor and headed for Argentia, Newfoundland with the Iowa and three other destroyers in our squadron. The five ships would go out into the Atlantic, away from land, and the Iowa would fire it’s several 16 inch guns at targets for practice, what a tremendous sound it was when those guns went off.

Newfoundland was a very pretty country- very green with tall timber everywhere and clear cold mountain streams. We had a chance to enjoy the scenery when the captain planned a picnic for the whole ship’s crew (except for a few who had the duty assignment that day).

I found that my brother in law’s ship, the Albemarle, a Navy Submarine Tender, was in the harbor, so I went over to visit Lucille’s brother, Ed McPherson, and we had dinner together.

Apparently the Navy determined that the Iowa was ready for its first mission, so the ships headed for Norfolk. We were docked not too far away from the Iowa and could see that some carpenters were constructing a wooden structure on one of the decks. We later found out that it was to accommodate President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his wheel chair. The President was to be taken to Casablanca, North Africa and then to Teheran, Iran for a conference with the “Big Three”, Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin. Our destroyer group was then sent to Bermuda, awaiting the Iowa. Another squadron of destroyers would escort the Iowa to Bermuda, we would take over from Bermuda to the Azores Islands, and a third squadron would escort the third leg to Casablanca.

One of the first messages we received from the Admiral on the Iowa was “Do not use Iowa as target for torpedo practice”. A torpedo-man on one of the group of destroyers escorting from Norfolk to Bermuda had inadvertently released the safety latch and when he pulled the lanyard in practice, a torpedo was launched, but luckily it missed the Iowa. We never heard about the rest of the careers of that torpedo man and his captain.

We stopped in the Azores to refuel, then on to Gibraltar, then to Casablanca where we joined the Iowa (which had disembarked the President) for a voyage to Bahia, Brazil. I guess we had to “stay busy” while the conference was going on. There had been some sightings of German submarines in the South Atlantic and so we kept an eye out for them. We returned to Casablanca and escorted the Iowa on the return leg to the Azores. Our destroyer group then headed for Boston.

We were to be in Boston for several weeks, so Lucille quit her job and joined me there. My younger brother William, who was a soundman on a Destroyer Escort, docked in New York Harbor. Somehow he found out that my ship was in Boston and surprised us with a visit. We were very glad to see him, had dinner on my ship and then he had to head back to New York as his leave was up in a few hours.

Lucille headed back to Gulfport. In a month or so it was Christmas and I too headed home by train for about a week of leave, then back on the train to Boston. But in the meantime orders had been sent to my parents home in Long Beach, but arrived after I had left for Boston. As soon as I arrived aboard my ship, I was told my orders were to report for a month’s special training in tracking planes and ships at a radar school on St. Simon Island near Brunswick, GA. I quickly called Lucille to meet me in Brunswick in two days. You guessed it she quit her job and headed east. We rented a room in a home on the Island. It was a cold January and the island home was built to be a “summer” home, so we stayed cold most of the time.

Lucille developed a bad cold (or maybe flu) just as I was completing my month’s training. In the meantime, my ship had moved to Norfolk, so with her feeling very bad we headed by train to Norfolk. Officers’ wives could stay for a few days in the Chamberlain Hotel on Old Point Comfort, located on the north side of Norfolk harbor. I did not have duty aboard my ship the first night back, so I could spend time with Lucille in the hotel.

I developed a terrible pain in my stomach and walked the floor of our hotel room all night. In the morning we went to the Naval hospital and it was determined that I had a bad appendix and needed to be operated on immediately. The operation was successful, but Lucille had to find another room in town as her limited days at the hotel were used up.

She found a room, however bus transportation to the hospital made for a long ride, but she came to see me every day. We had visions of two or three weeks of recuperation before reporting back to the ship, but that did not happen as my ship was to leave for the Mediterranean in a few days and I was to be aboard. The doctor said I could tape heavy gauze over my scar for protection in heavy seas and he was right, as I had no more problems from the operation.

Lucille left for MS and I left with my ship headed for the Mediterranean to the port of Oran, Algeria. Shortly after we arrived, it was reported that two merchant ships had been torpedoed off the coast and the Rodman and another destroyer were sent to try and find the German submarine.

Shortly after night fall, we arrived in the general area where the submarine was probably headed and spotted something on the water not very far ahead of us and the Captain ordered our large spot light (which was high up in the air on our mast) turned on and immediately ahead of us there was machine gun firing into the air toward our spot- light, but it stopped very quickly. (Later the German Submarine Captain told us that they had just surfaced to recharge their batteries when they saw the spotlight. They thought it was coming from a seaplane, so they fired up in the air. He immediately realized it was a destroyer and he ordered such a steep dive back under the water that they very nearly did not pull the sub out of the dive).

We and the other destroyer continued to track the sub and attack it by dropping depth charges, but it was very good at eluding us and this went on all the next day and the next night. At about 8 o’clock on the second day of our chase the submarine surfaced a short distance away. Our gunners began firing, but our Captain ordered a cease- fire as he could see that the submarine crew was abandoning ship. Both destroyers sent small boats over to the sub to pick up the crew. Some of the crew had been hit by machine gun shells but there were no major injuries.

Our rescue boat had picked up about 25 of the crew and the Captain. The submarine Captain told us that our depth charge attacks had opened up seams in his sub causing the sea water to start coming inside and his batteries were so weak that he had to surface and abandon ship. He also said they were headed for a port in Spain (which was a neutral country at that time) when we intercepted them. The sub was quickly sunk by gunfire from our two destroyers. I remember seeing it turn up on one end with the bow or stern up in the air and then it disappeared below the surface of the water.

Our chief cook prepared a meal for lunch that day of sauerkraut, hot dogs and potatoes, about as close as he could come to a German meal. I traded two cartons of cigarettes with the submarine captain for his jacket with the Nazi insignia on the shoulders. He knew he would be exchanging his clothing for a prisoner of war outfit before long. We turned the Germans over to the proper authorities in Oran.

(Sometime after the war was over, someone who had been on the Rodman did some research and located where the submarine captain lived in Germany. He was invited to attend our ship’s reunion of the officers and crew and he accepted. He has attended several times. A few years ago he and several of his officer attended the Williamsburg, VA reunion, which is where I met him for the second time. At one of our sessions, I presented him with the jacket he had traded to me 50 years ago. Upon examining it he said, in pretty good English, that he did not think it belonged to him. If that’s the case, I said to him, when he returns to Germany he should call a meeting of all his officers and see which one impersonated the Captain back at our last meeting in the Mediterranean. He laughed and it was an enjoyable visit.)

We stayed in Oran overnight and the next day received orders to proceed to Plymouth, England, to prepare for the invasion of Normandy, France.

We left Plymouth in the late afternoon of June 4, l944. Our mission was to escort a convoy of landing craft across the English Channel. We headed out of Plymouth going Northeast leaving the English coast on our port (left) side. My assigned duty was to be on the Midnight to 4am watch, so I felt like I should try to get a few hours sleep before going on duty. I left a call to be awakened at 11 pm. I slept until about 10:30, went out on deck and noticed that land was on our starboard (right) side. I was then told that the invasion had been delayed for a day due to rough weather and we were returning to Plymouth.

In the late afternoon of the next day, we started out again for Normandy. All during the late night we could hear planes going over us. Later we learned that the planes were carrying paratroopers to be dropped behind the German lines. We arrived at Normandy (Omaha Beach) about noon of D-Day, June 6, l944. The escorted landing craft headed for the beach while we were assigned as one of the 20 or more destroyers to screening duty, which was to try to protect all the ships in the landing area from German submarines attacking from the English Channel. It was an amazing sight, all of the hundreds of ships and water craft between us and the beach and our aircraft flying over us.

When we were at “general quarters”, that is all personnel at their battle stations, I was the officer in charge of operations in the C.I.C. (Combat Information Center) located a deck below the Bridge, where the Captain was located. We had several radar machines to track ships and airplanes in our area and a sound machine to track submarines. We were in voice communications via a tube with the Captain’s station on the Bridge above us. Also, we had a short range radio repeat speaker, which meant we could hear any messages going to our Captain. Each night we could see on our radar screen, the German PT boats leaving the Cherbourg peninsula heading in our direction and the British PT boats going out to meet and do battle with them. We watched until the two radar blips merged and then we could hear the British yelling and their machine guns blasting. After a bit the foes would lose each other and then head back to their homes to await another night battle.

A few German planes would come over the beachhead every night, sometimes dropping bombs and sometimes just passing over to keep us at our battle stations instead of sleeping. One night our gunners were credited with shooting down one of the German planes.

Another day I was out on deck and heard a very loud explosion a few hundred yards astern of us and as I looked I saw that a large landing craft had been blown up with the bow and half of the craft going one way and the other half going in the opposite direction and then each half dumping the trucks, equipment and men into the water. Apparently, one of the German planes, the prior night, must have dropped a bomb with a delayed fuse and when the “third” ship or watercraft passed over it an explosion happened. We sent our small boat over to help pick up survivors and brought them aboard for our ship’s doctor to treat them. Some who were found to be very badly wounded were carried to a nearby hospital ship.

After a number of days “screening” the landing area, we were ordered back to England for supplies, food and to refuel, and then to participate in the bombardment of Cherbourg.

On June 25th a Task Force consisting of two U.S. Battleships, two U.S. Cruisers, two British Cruisers and a group of U.S. and British destroyers steamed into the area of offshore Cherbourg, France. Part of the American Army had moved toward the south and were now moving down the Cherbourg Peninsula. We were to bombard the shore batteries while the army moved toward us from the East.

From CIC we determined the miles to the shore batteries, passed this information to our gunnery officer, who set the range and started shooting all four of our 5’ guns toward the target, along with the rest of the Task Force. There were a lot of shells hitting that part of France.

The Admiral of the Task Force ordered our ship only to go closer toward the shore, so that as the German batteries fired at us, the larger ships could blast away at the puffs of smoke giving away the positions of the German artillery. This we did and pretty soon the German shells were falling just short and just over us and the Admiral had seen enough and he said to our Captain over the short range radio, “get the hell out of there, are you trying to be a hero?” That’s all our Captain needed and we laid down a smoke screen (smoke messes up the range finders for the shore batteries) and hid behind it as we went full speed and high tailed it out of range of the Germans.

We headed back to England but were re-routed to Belfast, Ireland for a couple of days visit before going to the Mediterranean for the eventual invasion of Southern France. On the way, we stopped in Palermo, Sicily for a day or two. A few hours of shore leave allowed us to visit the catacombs, the subterranean burial chambers of the early Christians, which was very interesting. Then we moved up past Rome, past the Isle of Capraia, as the Allied Army was now in Northern Italy and had captured some of France along the coast near the Italian border.

The Southern France invasion was near St. Tropez on August 15, 1944. Our task was to support the pre-invasion mine sweepers, which took us very close to the shore. Just before the bombardment was to start, our Captain saw a German gun position fire at us, so we returned the fire and therefore had the honor of firing the first shot in the invasion of Southern France. The other members of the task force consisting of a U.S. Battleship, U.S. and French cruisers and destroyers also began firing. It wasn’t long before all resistance had ceased and the Allied troops that landed were moving very fast toward Germany.

In fact, things were so quiet the next day that the Captain allowed swimming off our ship as a celebration. French forces had taken over the port of Toulon and we had a quiet visit there. Harry Gustafson, one of our gunnery officers and I had about a half day shore leave to investigate the town. I found a German prisoner who was selling his pencil drawing of the Toulon harbor, which was very good and I purchased it from him. He signed it for me and we headed back to our ship. A short distance from our ship was a small house near the shoreline and so we decided to check it out. We found it was abandoned but on the porch facing the water was an Italian machine gun set up ready for action. The two of us carried it back to the ship. We got to thinking how we would look disembarking in some U.S. port with our treasure, so common sense prevailed and we quickly sold it to one of the crew for $l5 and split the money.

The last stop along the French coast was in the port of Marseilles, where I found that the ship of a good friend of mine at Tulane was anchored in the harbor. He of course was surprised to see me. We both knew we were in the Navy, but not the area. His hometown was near Shreveport, LA.

It was during this time that I heard our Executive Officer, No. 2 in command and our navigator, complaining about having to get up each morning before daybreak when we were at sea, to take star sights to determine our position. My course in navigation at Tulane was my favorite R.O.T.C. course, so I told him I would be glad to accept the extra responsibility as navigator and that’s all it took. From then on for the rest of the time I was aboard the Rodman, I was the navigator. The star sights are taken each morning before daybreak and each night after sundown. The nautical instrument you use is a sexton. Also a watch and a special book are needed. You sight the star with the sexton, sit it on the horizon, and mark the time of your reading at what angle the star was above the horizon. Later you go to the special book, which would tell you the latitude and longitude of your position in the world. You would quickly sight another star in another direction and take a reading. Where these two sightings crossed on your navigational chart would be your position. Then you would correct your position on the ship’s chart. The young sailor Quartermaster John Hunt, who worked with me as navigator’s assistant, was an excellent help. He always had the proper charts ready, the sextant cleaned and many other things to make my job easier.

The Rodman was ordered, in late October, to return to the Boston Shipyard for overhaul and conversion to a Destroyer-Mine Sweeper, which meant removing some of our equipment toward the stern of the ship, so as to compensate for the weight of the mine sweeping gear being installed.

Lucille and I had not seen each other for about six months and I missed her very much. We had tried to write about every week or two. She said sometimes some parts of my letters were cut out, when apparently the censors thought I had written something that they felt might help the Germans in some way.

When we arrived in Boston, I called Lucille to tell her we would be in port for several weeks, and you guessed it, she quit her job and came to Boston.

After the mine sweeping gear was installed, our ship moved down to Norfolk and the wives came down by train, since it was expected that we would be in Norfolk a few days. Our ship would go out of the harbor to the open sea and practice putting the mine sweeping gear in the ocean and bringing it back on to the ship. We also had some days firing at targets being towed by small planes. On our last day in Norfolk, as we reentered the inlet leading to the harbor, the fog was so thick that you could not see 10 feet in front of you. We had to use our radar to pick up the buoys marking the long harbor entrance and just crept along until we anchored in the harbor. It took us about 3 hours to come from the ocean to the harbor, which time normally would be about half an hour. The Captain sent a small boat of a few men to test whether it was practical in such thick fog to ferry the crew ashore.

It was Christmas Eve and our wives were over in the Chamberlain Hotel awaiting our arrival. In daylight and no fog the hotel could easily be seen from our ship. The small boat got lost in the fog and did not return. It was now late afternoon and with the fog, and nightfall coming, the captain made the decision that there would be no shore leave this night. It was a very disappointing Christmas Eve. We did have shore leave on Christmas day.

In a day or so we headed for the Pacific. Lucille and I had another tearful parting (it would be another 6 months before we would see each other again). Our ship went through the Panama Canal on January 5,1945 and on to San Diego, then headed for Seattle, when we picked up about 10 or so cargo ships, which we would escort to Hawaii, trying to protect them from Japanese submarines. There were about 3 more destroyers with us.

The trip was uneventful, except one day the last cargo ship, of Dutch registry, kept dropping farther and farther behind the other ships, even after messages were sent to keep station. So our captain said he would try something that might make the ship stay in position. So he ran up a black flag on our mast, which meant we were attacking a submarine, pulled our ship out of position, dropped a few depth charges, which exploded with a loud noise, sending water high in the air. About that time we could see some heavy black smoke rising from the Dutch cargo ship, and in a short time it was back in proper position with the other ships. We had no more trouble the rest of the way to Hawaii with that ship lagging behind.

Lucille and I had a secret code between us which we prepared before we left Norfolk. The names of some of the boys in my high school class were used to identify what Pacific island the Rodman would be visiting-

- Gene- Hawaii

- Ray- Guam

- Houston- Marshall Islands

- Pete- New Zealand

And several more

I was to write that I saw “Gene” on such and such a day, which meant we were in Hawaii. The code worked pretty good. Lucille would call my family to give them the same information. (The statute of limitations has now run and I cannot be prosecuted for telling such secrets☺.)

We docked in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and replenished our supplies first, then it was time for shore leave. Four of us decided to head for Waikiki beach for a swim- Harry Gustafson (gunnery), Wally Sandner (engineer), Gene Cohen (communications) and me. After a good swim we went to the Royal Hawaiian Hotel, which was right on the beach to see if Wally could find a piano to play. In the ball room, we found the piano and Wally was in “hog heaven”. He could play anything- all from memory. Before long there was a crowd of 50 or more people who wandered in to listen to Wally’s music. After about 3 hours of great music and singalongs, Harry and I headed back to the ship. Wally and Gene did not return until around Midnight. The next morning Wally had blisters on his fingers from playing the piano so long the night before.

In a day or so our ship went out of the harbor to an uninhabited small island where we practiced firing our 5 inch guns. Then another day we went out of sight of land to practice firing at targets in the air, being towed on a long line by small airplanes. After many hours of practice and running up and down the ocean for miles, the captain said we were through and he wanted to head back to port as quickly as possible, as he had a special engagement that evening. As Navigator, I had gotten a sun line at 12 noon, which meant by using my sextant, I had set the sun down on the horizon, and knew we were on a North-South line, but did not know how far we were East or West of such line. Reviewing the chart, I noticed there was a large underwater reef marked on the chart between where I thought we probably were and Pearl Harbor to our Northwest, so I told the captain we should go more South several miles and then West and then head for Pearl Harbor, which was a much longer way but a safer route. He was not a happy camper with that answer, but after grumbling some he told the helmsman to head South and so on. Another destroyer was with us and it took a different route to the harbor. We arrived late but safely in the harbor, but heard that the other destroyer took the shorter route and hit the reef and damaged one of its two propellers. It was two weeks catching up with us because of the propeller repairs. The captain never mentioned the long route or “short cut” reef incident with me- just as if nothing had happened.

We knew we were heading for an invasion of a Japanese island, but we did not know which one. Our first stop out of Hawaii was on the island of Kwajalein, in the Marshall Islands, about 2,500 miles from Hawaii, then on to a small group of islands, Ulithi, below Guam, about 1,000 miles from Kwajalein. We stopped there only for fueling and to pick up supplies, as this would be our last stop before the invasion of Okinawa, the large Japanese island at the southern end of a trail of islands south from Japan proper, called the Ryukyu Islands, about 600 miles from the main island of Japan.

Our ship joined a large group of ships in the ocean below Okinawa for a couple of days and at least one night. The 20 or so destroyers encircled approximately 15 larger ships (battleships, cruisers, and there may have been one aircraft carrier. It was a dramatic picture on our CIC radar screen- almost a perfect huge circle of destroyers surrounding the big ships. As the Admiral ordered a change in direction, the whole fleet would move to the East and the North and so on. It was a massive show of power daring the Japanese to attack. All ships then steamed away to their new assignments.

Our orders were to head for Okinawa, arriving about March 24. On our way we picked up from the ocean two Japanese pilots who had been shot down and were later turned over to Naval Intelligence.

We were to dock in Kerama Rhetto, the small island group just about 5 miles southwest of Okinawa, which was captured some days before the main invasion, and was to be used as a forward base for the invasion. The actual mine sweeping operations turned out to be rather uneventful. Each night a Japanese airplane would fly over the area just to keep us from sleeping.

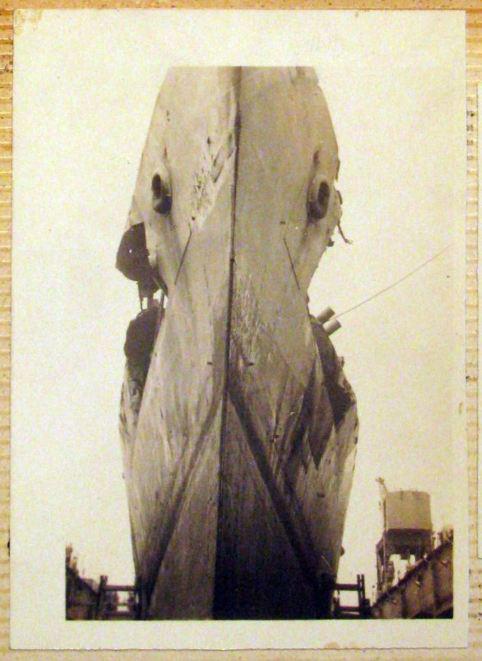

The events of the afternoon of April 6 make this day the most eventful one in the Rodman’s history. We were conducting minesweeping operations off the Northeast coast of Okinawa. Most of the crew had not been ordered to their battle stations as the day’s activities had been very quiet, but suddenly about 15:30 (3:30) in the afternoon, two Japanese suicide bombers came over the small hill of an island just a few thousand yards ahead of us. Very quickly several of our gunners opened fire on the oncoming suiciders. One crashed through the forecastle (toward the bow of our ship) into the forward living spaces where a split second later its two bombs exploded, bursting open the deck on both sides of the ship to the waterline. Some compartments were completely demolished. Sixteen men were killed. Another plane struck the superstructure penetrating the bulkhead of the captain’s cabin, which made it impossible for me to get to my battle station. There had been a bad oil spill back near the stern, so several of us moved back there to try to clean up the oil before fire ignited it. While back there, I saw a suicide plane shot down by our gunners, land in the water close to our ship and flip over, causing one of it’s wings to hit the starboard side of our ship. The Marine air group had been notified of the attack on us and came to our rescue- I saw a Marine flying a Corsair right on the tail of a Japanese plane, fly through our anti-aircraft fire and knock down the enemy plane. Fires had broken out in the forward part of the ship, almost completely gutting the superstructure within. Nearly all the men whose battle stations were on the superstructure were forced over the side by the flames. In the meantime, while still trying to clean up the oil spill, the gunner just above us pulled off his headset and yelled that the Capitan said, “abandon ship”. Everyone in our area grabbed the available life jackets and went overboard, including myself. After hitting the water, I noticed a young officer who had just come aboard our ship swimming without a life jacket, so I loosened my jacket and we shared it. It kept us afloat. We had been warned that some of the enemy planes had strafed men in the water, so every time we would see a Japanese plane heading our way, we would duck under the water and hold onto our life jacket with our arm extended upward. The fight continued for two more hours.

It was estimated that at least 25 enemy planes had been in the attack. The small minesweepers that we had been trying to protect, as they swept, picked up about 150 men from our ship. In the meantime, our sister ship, the Emmons, had been hit by 5 Kamikaze planes and several bombs. One bomb hit her magazines, which exploded, fires got out of control and she had to be abandoned. All personnel in her C.I.C. room were killed. The small minesweepers were busy picking up the living crew members. The floating wreckage of the Emmons was finally sunk by our own planes as it was a hazard in the waterway between the islands.

When a ship is being abandoned there is always an assigned “skeleton” crew who stay aboard with the captain and are the last to leave. I was not assigned as a member of this group. We were told later that David Caldwell, the damage control officer, and his group were making such good progress in putting the fires out and shoring up bulkheads to keep the water out of spaces below the waterline, that the captain reconsidered and decided that the ship could be saved, provided she did not take another serious hit. The ship then limped into the island group Kerama Phetto, just about 5 miles southwest of Okinawa. We who had gone overboard were picked up by the small minesweepers. We were returned to our ship the next morning.

Our doctor, while working on the wounded in the darkened officers wardroom, remembered sitting on what he thought was a fire extinguisher that he figured had come loose from the bulkhead, but in daylight, it was revealed that it was an unexploded bomb dropped by the plane that hit the superstructure. Also this same plane was carrying two pilots- one short and one about 6 feet tall. We were wondering why two pilots? Our most imaginative explanation was that the second pilot was an observer who was to report back to the homeland how the suicide operation was carried out, but the other pilot double crossed him and took both of them to their deaths.

Our gunners, with the help of the marine pilots, were credited with taking down 11 enemy planes.

After emergency repairs were completed, we headed back to the states for complete repairs. The main steering mechanism located on the bridge was messed up so we had to use our emergency steering, which was located below decks near the stern. The helmsman, while steering the ship, was facing the stern (opposite to the direction in which the ship was to go). It worked and we headed back across the Pacific to Charleston, S.C., as all of the shipyards on the west coast were full of ships needing repairs. About this time we were glad to hear that the Germans had surrendered in Europe and maybe this war would be over before too long.

Our first stop was in Guam. I had information that my high school friend, Ray Dubuisson, was stationed there, so I bummed a ride in a jeep to the Medical station, as Ray was a seaman in the Navy Medical Corp. We had a good visit. Ray went on to become a medical doctor in Nashville, TN after the war ended. Lucille got a message from me that I had seen Ray, which via our code meant that we were in Guam. She let my family know.

Next stop was Hawaii, then on to San Diego, the Panama Canal and Charleston Navy Yard. I called Lucille to tell her we were expecting to be in Charleston for over a month for repairs, and you guessed it, she quit her job and came to Charleston. I found a small, furnished house for rent in the old part of Charleston and we were very comfortable there.

The repairs were moving along very rapidly and there was some information around that predicted our ship would be involved in the invasion of mainland Japan some time around the first of November. However, the atomic bombs were dropped on Japan in early August and Japan surrendered. What a happy day that was. Lucille and I headed for the Methodist church not far away and gave thanks to God that the war was over.

When I joined the Methodist church as a boy of twelve, I took seriously my promise to follow Jesus Christ’s teachings and try my best to live a Christian life. There had been many times during my Navy experiences that I was frightened, but the calming knowledge that I had read, was told and knew that God, through Jesus Christ, was always with us, pulled me through.

Lucille headed for Mississippi and I did the same in October when my Navy days were over. We could now resume civilian life with the war behind us. The three plus years of active duty in the Navy were a small price to pay for the protection of freedom over much of the world, and particularly our land and our way of life. We should all strive for and continually pray for peace throughout the world, so that young men and women will not have to go through the wasteful hell of war in the future.

Leave a Reply; Join the conversation